How We Work at PSPDFKit

Table of contents

Since PSPDFKit’s beginnings in 2011, we’ve had to reinvent the way we work many times. Transitioning from a company consisting of a single person to one with more than 40 people requires change, and even more so when expanding from just iOS to Android, Web, Windows, and macOS.

That said, our biggest concerns have always been maintainability and long-term code evolution. PSPDFKit crossed the 1 million lines of code boundary long ago, and there are still quite a few features in the PDF spec that we want to support. At this size, and with millions of people constantly using our products, we cannot do a “grand rewrite” every few years. That said, some code we ship was written in 2009, and it still works just as well today.

SDK != App

Developing an SDK has unique challenges that often do not need to be considered when writing a typical application. Since our SDK is integrated into thousands of apps, people expect our API to be consistent, and ideally it shouldn’t ever change (unless someone runs into a specific limitation). We take great care to evolve our API in a meaningful way, and often the design is forward-thinking so that future extensions are easier.

Most of these lessons aren’t unique to an SDK, but they are applicable to any large software project. Once your code has many consumers, you will need to be more conservative or else face the backlash of fellow developers having to constantly update their code with every release (or, more drastically, simply stop updating your dependency).

API Evolution and Cross-Platform Considerations

PSPDFKit started on iOS, but over the years, we have conquered one platform after another. Our challenge to this day is finding a compromise between platform-idiomatic APIs and building common patterns across all platforms. It’s rare that we get an API just right on the first try, but our process is designed to attempt to close that gap, in that we identify a set of requirements and common needs and try to structure the interface as idiomatically as possible. Most of our partners implement our SDK across their app’s landscape, which usually is at least iOS, Android, and Web, and sometimes also Windows or even Electron. We structure our teams based on technology and not on specific features, so this is a particularly difficult challenge. About a year ago, we introduced proposals as a better way to plan features long-term.

Proposal-Based Development

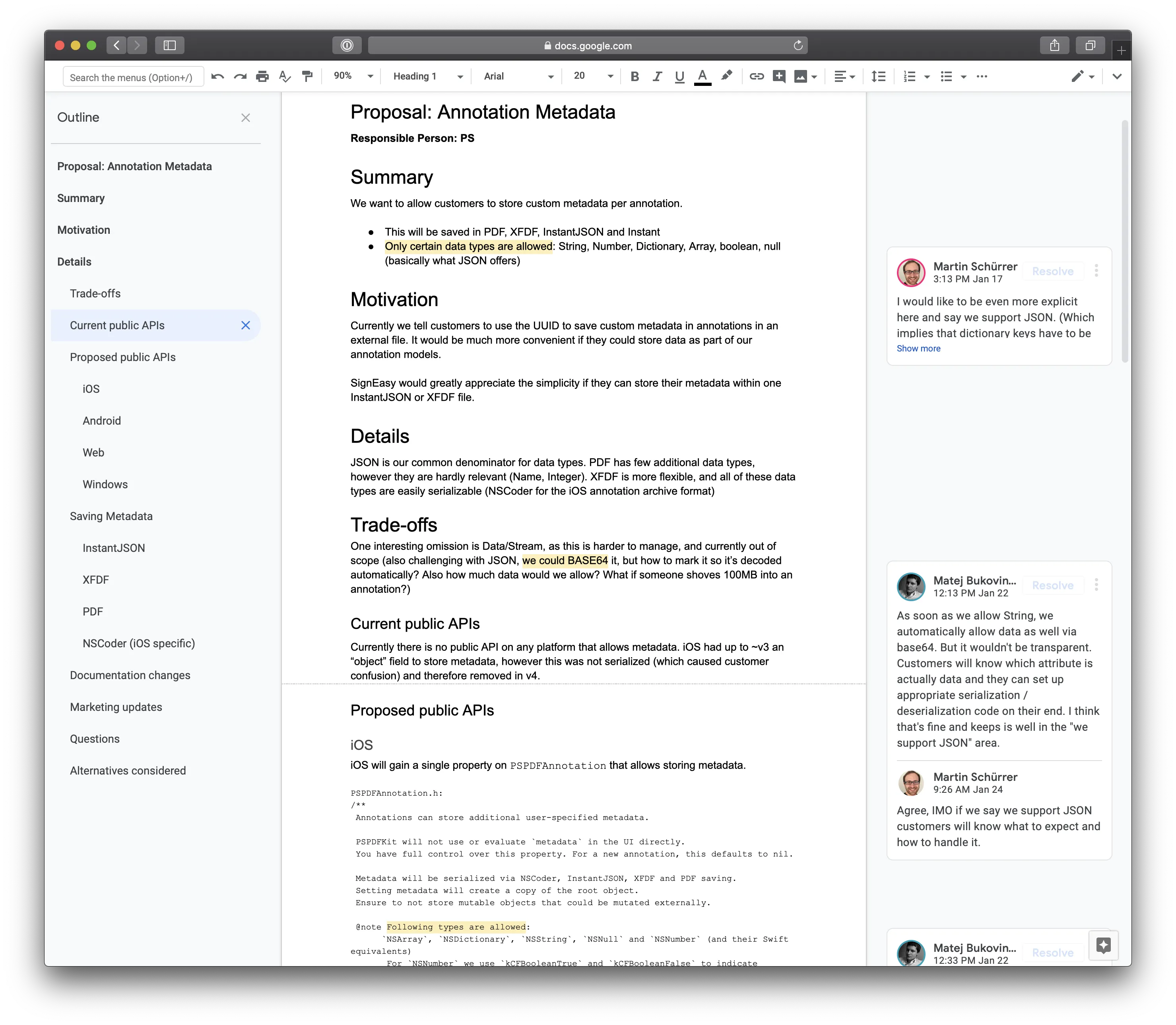

Almost every feature we build at PSPDFKit starts with a proposal. Proposals are documents where we define what we want, in addition to outlining the API for each platform — even if we don’t plan to bring a feature to all platforms at the same time. Most new features start with an implementation in C++, our shared core that is used in every single platform. In the past, we usually began with the iOS implementation, which often made the Core design suboptimal for other consumers or challenging to map to Java via JNI and Web via WASM and PSPDFKit Server. With proposals, we usually catch these kinds of issues in advance, which leads to an improvement in the overall design for all platforms.

A proposal includes the following sections:

- Summary

- Motivation

- Details

- Tradeoffs

- Current public APIs (all platforms!)

- Proposed public APIs (all platforms!)

- Further details based on proposals

- Documentation changes

- Marketing updates

- Open questions

- Alternatives considered

Each proposal has a person responsible for moving the process along. The author might not be able to answer all questions and sections on their own, but that’s completely fine. The proposal author will usually write what they know and then ping a few people that they know are most involved to help with areas they are unsure about. They will then keep on discussing the various parts until all major questions are sufficiently addressed and the proposal is accepted.

Feature Planning

Deciding which feature to tackle next is really hard with a product that has so many different use cases. Customers who primarily use PSPDFKit as a magazine viewer might ask for linearized loading or page curl transitions, while a pilot on an airplane is mostly interested in fast search, and board meeting members want efficient and easy-to-use annotation tools. Meanwhile, customers on PDF Viewer might ask for split-screen mode or page cropping — something we basically never hear from our B2B partners.

Managing all these data points used to be a difficult task, and while we made notes and tried to categorize emails, Intercom messages, Zendesk tickets, and information from sales calls, it was very hard to reconcile everything. Then, about six months ago, we introduced productboard(opens in a new tab) as a common platform for compiling all of these data points. productboard calls them Insights, and now every single employee submits Insights from customer interactions. Then we aggregate and categorize these text snippets into the features they represent. With this work, we can now sort through and easily see what the most requested features are per platform. Insights retain the original request text, so we can click on any feature and read the exact text people used to request such a feature, and the text often includes additional details that help us to build the right thing. Implementing productboard into our feature planning has already improved our 2019 roadmap, and we expect this process to become even more important as we collect more and more data points.

Refactorings as Roadmap Items

productboard only collects features and enhancements. However, a healthy software product needs refactorings as well. We preach the Boy Scout Rule to “leave it better than you found it,” and we do smaller cleanups with almost every PR. This does make code reviews somewhat more challenging, but for us, it’s by far the best way to keep a codebase fresh. The way we write code has changed over the years, and it’s not realistic to update the entire codebase every time we learn a new trick, so it makes sense to do this gradually as we work on individual subsystems.

Learn More: What Is Ninja Refactoring, and When Should You Consider Doing It?

Larger refactorings are part of our roadmap, and planning these is especially useful for controlled API evolution. We align our native SDK release schedule with Apple and Google, posting major updates once a year; these updates also often include both a larger set of API refactorings and the deletion of deprecated APIs. Unlike Apple, we do not need to be binary compatible, so we have the luxury of eventually deleting old mistakes and maintaining a clean, logical API design. We usually do not remove deprecated methods outside of major releases, but sometimes a redesign is simply impossible to map to old APIs. For these cases, and really even if we offer deprecated fallbacks, we write migration guides that aim to make upgrading as simple as possible. These guides explain how the APIs have evolved and how the replacement calls work.

Pull Requests/Merging Code

We use the typical pull request-based GitHub workflow, so I won’t go into all the details here. Our goal is to always have master in a shippable state, and we offer nightly access to our partners on a per-request basis. This is extremely useful for us as it can give us early validation of a new hook, a new feature, or a bug fix requested on support.

Releases

For releases, we adopted a loose variant of the release train, with the goal of shipping a minor release every eight weeks. This is enough time to push larger changes, and it’s often enough time to keep a high pace of shipping. Between minor releases, we create patch releases approximately every two weeks — sometimes more, sometimes less. Patch releases should never have breaking API changes or breaking behavior changes. We mostly manage to stick to this goal, with the occasional bug fix that is simply more important than absolute behavioral stability. Adding new APIs, while not a goal for patch releases, is something we sometimes do if there’s a strong need from a customer.

Release Bot

Next to the obligatory release checklist, we try to automate as much as possible, so releases can be triggered directly from Slack with Release Bot. It supports choosing a branch and then reports back with the status, as a Jenkins worker spins up and starts to test and ultimately builds an archive that we upload to either Apple (for PDF Viewer) or our own licensing backend (for the SDKs).

Backporting

Pull requests that fix bugs or are pure feature additions are marked with backport tags based on the developer’s or reviewer’s perception of backportability. However, some fixes are so extensive that the risk of backporting is too high. Ultimately, these tags are merely suggestions for the release builder. One person branches off the last stable release and cherry picks one PR after another. If there are problems or a merge is too complex/risky to solve, we simply skip the backport. All other PRs get a “backport done” label to indicate that we indeed backported the patch.

Our partners always get the internal issue number on support once we have a reproducible test case and plan to fix a particular issue. In this way, they can easily track if a specific patch release already includes their fix, or if it lands in the next minor version. This improves plannability for our partners and eases expectation management.

Once we release a minor version, we almost never backport to the previous version unless there’s a special requirement (for example, a security incident). A great example here is Android and our v5 release. We adopted AndroidX (the successor to the Android Support Libraries) quite early after hearing many requests from our partners. What we didn’t consider was the slow pace of hybrid technologies (such as Cordova, Xamarin, or React Native) moving to AndroidX as well. Without support there, we are unable to update our wrappers to 5.0. However, many of our customers do use such wrappers and still require timely updates and fixes. We already shipped a patch version of 4.8 that includes many bug fixes that have been released in 5.0 and 5.1, and we plan to continue doing this until The Apache Foundation, Microsoft, and Facebook finalize their AndroidX migrations. While it makes things slightly more difficult, for the majority of our users, this is an acceptable tradeoff for being cutting edge.

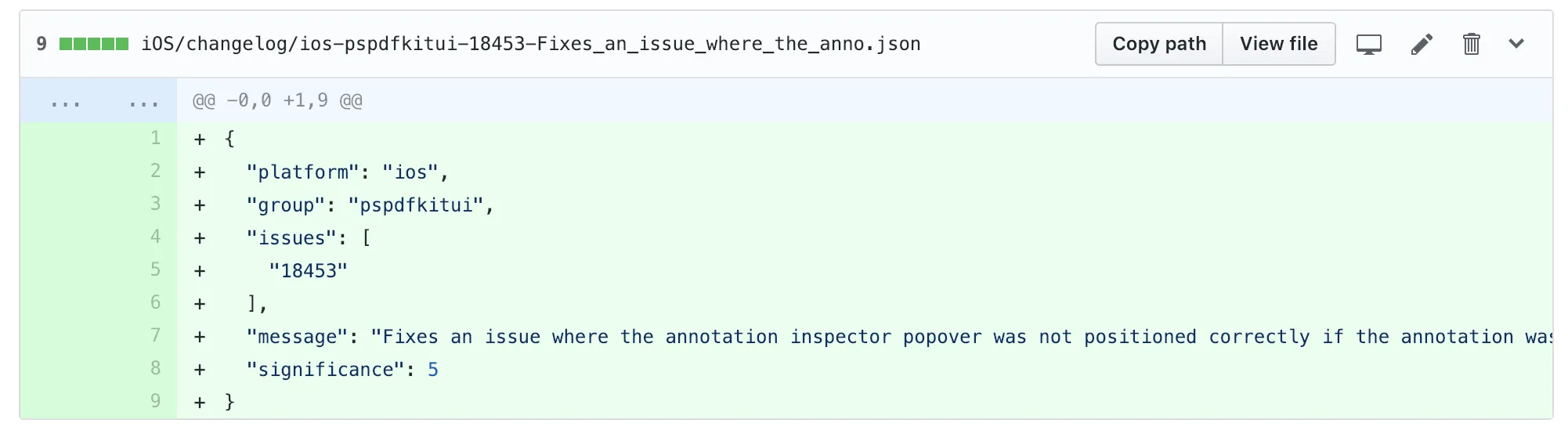

Changelog Management

Maintaining an extensive changelog is more complex than you might expect. Changes/improvements to Core impact many platforms, and with a backport, we do want to make sure we include the corresponding entries in our changelog as well. Furthermore, we categorize fixes into UI, Model, and — depending on the platform — additional categories. Merge conflicts in CHANGELOG.md were once so common and ultimately proved so annoying that one of our engineers started a new command-line tool as part of our Experimental Fridays. It was quickly adopted by all our platforms and greatly simplified changelog management. Changelog entries are now individual JSON files that include the platform, component, and priority, since we want to sort entries from most interesting to least interesting to make things easier for our partners.

Here’s how this looks:

bundle exec pspdfkit changelog add -g pspdfkitui -i 15077 -m “The home indicator on iPhone X is now automatically hidden when the HUD is not visible.”

Obviously that’s a mouthful, so we use an alias like cla and we auto-detect the platform (iOS in the above case) based on the subfolder. We use a big monorepo as our main development repository.

Monorepo

Just like Google or Facebook, we use one LARGE repository for almost all our SDKs. Learn more in our Benefits of a Monorepo post.

CI

Continuous Integration is really difficult to get right. We’re constantly fighting with Apple’s yearly OS updates, Xcode updates, NDK updates, Visual Studio Updates, Selenium updates, slow GitHub connections, random Jenkins worker disconnects, Jenkins upgrades, broken plugins, crashing Android emulators, and more. And I haven’t even mentioned flaky tests yet!

However, everyone who works on CI knows about these challenges, and with enough discipline, planned rollouts, and automation, this is very manageable. We use a mix of Mac Minis, beefy Linux machines, and Windows boxes. Windows was powered by Azure early on, but we ended up using dedicated servers, as it’s more cost-effective. Core tests run completely inside a well-defined Docker environment to reduce entropy and increase retestability. Core is pure C/C++ and only runs model tests, which execute blazingly fast. With Google Test, we can even run them concurrently on multiple threads.

macOS for CI proves to be by far the most difficult OS to manage. There’s very little support and there are some “security” features, such as Gatekeeper alerts, that cannot be clicked on when logged into via VNC. These require lots of creativity to automate. We use a sophisticated Chef cookbook that takes a pristine macOS to a full-blown test environment that can run iOS, Web, and Android tests and build our releases.

We look into other systems from time to time but they are either too slow (Travis), too restrictive and with an uncertain future (BuddyBuild), or not yet mature enough (GitLab).

Benchmarking

Detecting performance regressions or improvements is particularly important over long-running projects. Seemingly innocent changes might have a huge impact on specific platforms, and if this is detected months later, it’s often nearly impossible to pinpoint why there’s, for example, a 10-percent slowdown. Everyone on the team can trigger performance tests, and we use one specific Linux machine to benchmark Core, so there’s a stable baseline. This process isn’t perfect, as things often change with updated compilers or even kernel versions.

We also use iOS benchmarks that run on a Mac Mini in the Vienna office with an attached device. This setup has proven to be particularly flaky, as we can only automate so much on an iPhone, and ideally one would perform a complete device reset to get 100-percent reproducible test results. Running tests too often also greatly reduces the lifetime of iOS devices, which simply aren’t made for constantly being under load. We do hear stories of how batteries pop like popcorn in data centers where devices are automated. This is still an area where we want to improve.

Danger

PRs are automatically checked for certain requirements — most notably, we perform a simple spellcheck for the most common typos, and we check that the PR includes a changelog. Danger will automatically comment on the PR and update itself once this has been fixed, which saves time and ensures we do not forget changelogs. Certain patches might just include internal cleanup and not have any external-facing changes. In such a case, our engineers can set a skip-changelog tag. Danger will see this and skip the changelog check if such a tag is found.

Reviewbot

To ensure a fast turnaround time between opening and merging a pull request, we use our custom-built Reviewbot. It scans our repositories for pull requests that have the READY TO REVIEW or NEEDS FEEDBACK tags and posts them in Slack, one by one. It’s quite powerful and shows if a PR already has a review. Our Android team has a minimum of two reviews per PR, so Reviewbot knows that and treats this platform differently.

Conclusion

This post explained a few of the processes we use at PSPDFKit to build high-quality products. We’re constantly reevaluating and improving our internal workflows, so expect updates here in the future. If you have tips or something you read that you find valuable, I’d love to hear from you.