Effective process mapping guide

Table of contents

This is a guest series by Joanne Wortman, an independent business/technology consultant and freelance writer in the NY Metro area. She has almost two decades of experience providing business process optimization, organizational change management, M&A integration, and program management across many business sectors, with a concentration in manufacturing.

Once you've scoped and prioritized your business process architecture (as per our previous article), it's time to begin mapping out your business processes.

Good Intentions are not Enough

Motivated and engaged employees are certainly willing and able to improve the efficiency of their daily work. In many cases, they form self-organizing teams and work out solutions to process issues that result in real improvements. They discuss proposed approaches, whiteboard the process, and get back to work. Enterprise-wide process improvement proceeds best with some level of standardization and it may require the guidance and assistance of a business process specialist. This is especially true when:

- Employees may not recognize the unintended consequences of changing a process that is shared with other people, departments or divisions

- The workforce is unaware of organization's strategic direction and how that will be threaded through target state business processes

- Technology improvements are about to impose major disruption on current processes

- The people who do the work are unable to articulate the steps in a process in a standardized, linear fashion

Keys to Effective Process Mapping

A few simple rules provide a standardized framework for mapping processes effectively. Of course, you will begin with the scoping hierarchy we talked about in the last post. You will actually refine the hierarchy as you proceed through an enterprise process initiative, and that's perfectly normal.

It's said that brevity is the soul of wit, but it's also critical to creating understandable process maps by using crisp, precise language and a standard visual syntax of boxes, shapes, colors and arrows in a process diagram.

Follow these simple rules:

Each box on a process map should represent a single action or decision.

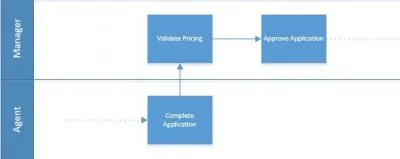

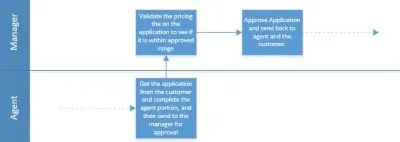

If the diagram uses swimlanes (also known as cross-functional flowcharts), the actor for each step is defined by the lane , not within the action or decision box on the chart. The box should contain simple verb+object phrases, with the to and from information implied by the arrows ending and originating on the box. Consider the following examples:

Right Way: Tight wording, verb+noun, single action in each box

Wrong Way: wordiness, multiple actions in each box, prepositional phrases that are redundant to visual syntax

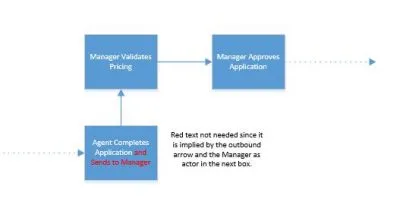

If the diagram does not use swimlanes, the verbal syntax is Actor+verb+object. The To and From information is still designated visually and does not need to be added verbally to the box. For example:

Right Way:

Wrong Way:

Other helpful rules for creating good process maps include:

- Use boxes for steps and diamonds for decision points.

- Label the exit points from a decision point or logic branch. Phrase these decision points as a question that can be answered with Yes or No whenever possible. For example:

- Is this a new customer?

- Is this a special order?

- Avoid crossing arrows whenever possible.

- Keep long arrows tidy by breaking direction in right angles instead of diagonals.

- For processes that involve complex logic and branching, break some of the logic branches out into separate diagrams. Too much information with too many decision points on a single diagram may confuse some audiences.

Current State Considerations

Historically, a business process initiative began with extensive effort devoted to mapping the current state, especially if the process team was a group of outside consultants. Today, it's more typical that teams abandon the potentially wasted effort involved in documenting "What is" and "What was" and jump right to defining and mapping a new target state process. If there is a solidly internalized understanding of how things work now, it's fine to skip the extensive documentation of the current state.

In certain situations, you should start by mapping the current state:

- You require current documentation for regulatory and compliance oversight and certification (Sarbanes-Oxley, HAACP, HIPAA, ISO, etc.)

- You know that inefficiencies exist, but you need to see the current big picture before you can begin an optimization attempt

- You have had or expect to have high turnover and you need solid current state documentation for training purposes

- You are about merge a newly acquired business into your existing business operations

The Importance of Mapping Process Variances

Naturally, the initial process mapping sessions will deal with the everyday transactions, or the "happy day scenario." Business inefficiencies arise when staff has to improvise a solution to an exception situation. Different workers will "wing it" in their own unique way. For example, when working through a purchase-to-pay process, one would document the standard workflow for receiving inbound shipments. The following non-routine situations also need to be documented, if not fully mapped:

- Receive an order shipped incomplete

- Receive an order with all the wrong items

- Receive an order with some items that were ordered and some that were not

- Receive an order with more than the requested quantity on the purchase order

- Receive an order after the requested delivery date

- Receive an order to the wrong receiving location

Each of these situations may add or change steps in the simple workflow for receiving in an order. Failure to properly understand and educate the workforce about them may result in payment errors or inventory inaccuracies that could have significant impact on the company's financial statements.

Defining Key Performance Indicators

You can't improve your business processes without a clear goal in mind. That's why we need to discuss key performance indicators at this point, although we will return to this topic in an upcoming post.

Consider the following story.

A customer service center puts together a team to work on the department's business processes and "improve customer service." They cannot dive in and propose new processes or new roles and responsibilities until they clarify what "improving customer service" really means.

Is it about reducing customer wait time in the queue? Is it about completely resolving a customer service issue on the first call? If it's about both, the team needs to realize that these performance indicators may be at odds with each other. Driving toward first call resolution may increase the time spent on that call, which may increase customer wait times if the staffing levels are not addressed as part of the improvement initiative. Reducing time in queue may only be achieved if agents hurry through the initial call and promise a callback with the requested information or resolution.

The effort to improve processes, or the quality of process outcomes must always start with agreement on the goals. Process teams may start with a mandate to improve quality or timeliness, or accuracy, but the goals must be stated very crisply with an actual target metric that can be measured and tracked.

Quality: Reduce the product defects to 1 defective finished assembly per 1,000 produced.

Timeliness: Close all financial periods within 5 days of month-end.

Accuracy: 99% of all orders will contain the correct items and quantities when picked for shipment from the warehouse.

With verbal precision established for these agreed upon KPIs, the process improvement team can better hone in on which parts of the process to improve.

In our next post, Process Optimization Fundamentals , we will provide specific suggestions for finding process inefficiencies and addressing them.