Beginner's guide to Docker commands

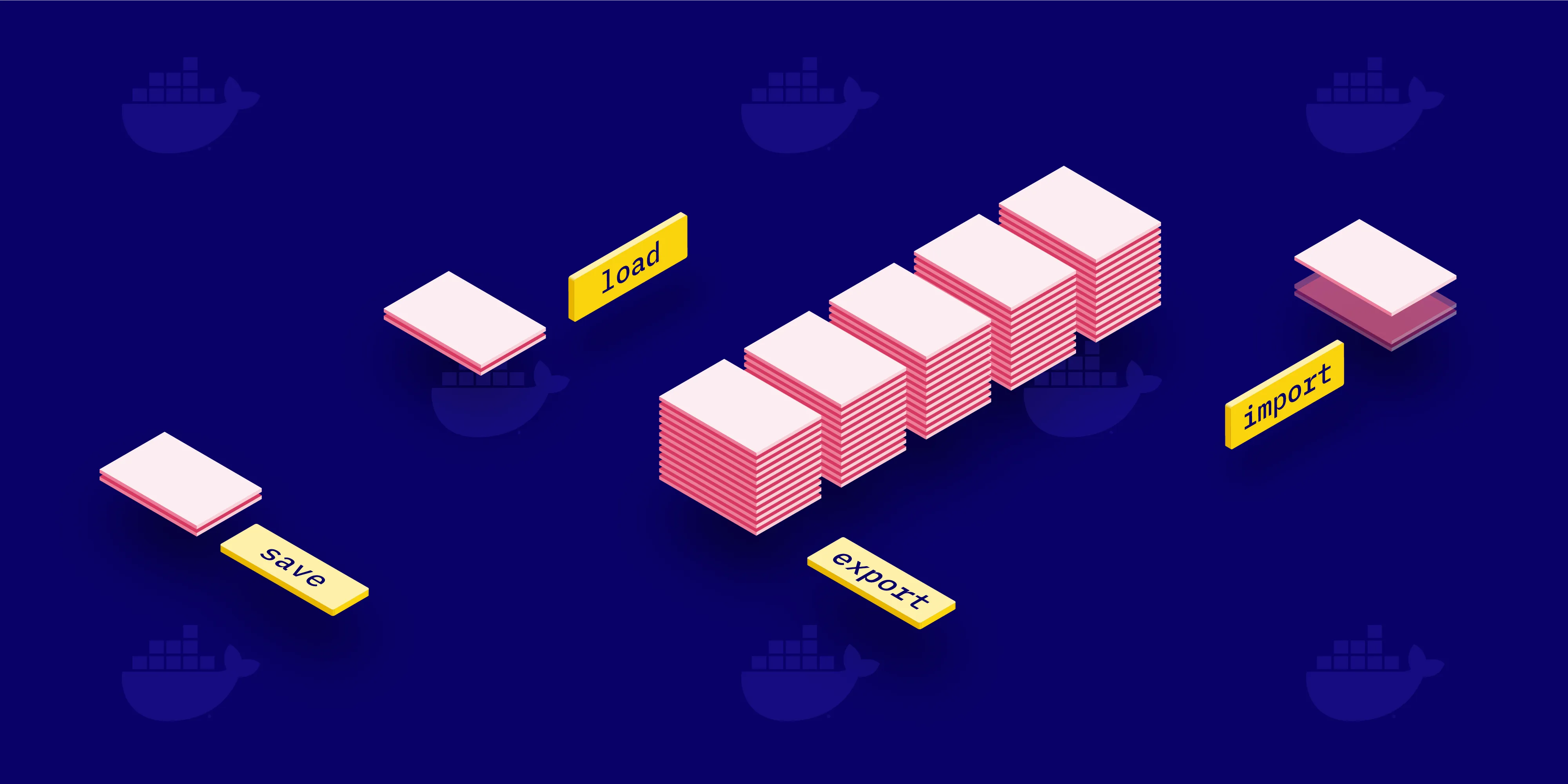

Docker provides four commands for transferring images and containers: save and load work with images, preserving layers and metadata, while export and import work with containers, capturing filesystem snapshots. Use save/load for transferring complete images with history, and export/import for filesystem snapshots or creating new base images.

This post will look at the differences between Docker’s import/export and load/save commands. It’s intended for relative newcomers to Docker and covers some of the basics, such as the difference between Docker images and Docker containers. By the end of the post, you’ll have a good understanding of getting both images and containers into and out of your local Docker registry. And if the Docker command help (shown below) is particularly confusing for you, then read on!

$ docker --help | grep -E "(export|import|load|save)" export Export a container\'s filesystem as a tar archive import Import the contents from a tarball to create a filesystem image load Load an image from a tar archive or STDIN save Save one or more images to a tar archive (streamed to STDOUT by default)Introduction to Docker

Docker is a powerful containerization platform that transforms how developers package, ship, and run applications. By encapsulating your application and its dependencies into a portable container, Docker ensures consistent behavior across environments, from development machines to production servers.

Unlike traditional virtual machines, Docker containers share the host system’s kernel, making them lightweight and efficient. This design enables faster startup times and lower resource usage compared to VMs, allowing developers to spin up multiple containers for rapid development and testing.

Docker’s portability guarantees that your application behaves consistently, no matter where it runs. This “write once, run anywhere” capability eliminates the notorious “it works on my machine” problem, streamlining development and deployment processes.

With its rich ecosystem, including Docker Hub — a repository of prebuilt images — Docker has become a cornerstone of modern software development. Whether you’re building microservices, deploying web applications, or managing CI/CD pipelines, Docker provides a reliable and efficient solution for containerized applications.

Docker images vs. containers

To master Docker, it’s essential to understand the distinction between images and containers. A Docker image serves as the blueprint for your application, containing everything needed to run it: the code, runtime, libraries, and dependencies. Images are static, read-only templates stored in registries like Docker Hub.

In contrast, a Docker container is a live, running instance of an image. Think of it as a house built from the image blueprint. Containers provide an isolated environment for running your application, ensuring it doesn’t interfere with other processes on the host system.

Here are the key differences:

- Static vs. dynamic — Docker images are static templates, while containers are dynamic, running instances of those templates.

- Multiple instances — A single image can spawn multiple independent containers.

- Storage — Images are stored in registries, while containers run locally and can persist on the host system until deleted.

Understanding these differences is crucial for effectively using Docker. Images provide the foundation, while containers bring your applications to life.

A basic Docker app

Let’s say you’ve created an app and you’re ready to package it with to share it with the world. You’ll do this by creating a Docker image. And for that, you’ll need a file named Dockerfile that looks like this:

FROM busyboxCMD echo $((40 + 2))First, you need to build the image:

$ docker build --tag calc .$ docker image ls

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZEcalc latest 5f3e5352a6e3 7 seconds ago 1.22MBbusybox latest db8ee88ad75f 7 days ago 1.22MBThen, verify that it runs:

$ docker run calc42OK, it works. But what if you send it to your colleague Alice? This is what the docker save command is for:

$ docker save calc > calc.tar$ rsync calc.tar alice@work:/tmp/Alice imports your image and runs it, logically expecting the docker import command to serve the purpose:

$ docker import calc.tar calc$ docker run calcdocker: Error response from daemon: No command specified.See 'docker run --help'.Oof. What happened here? In this contrived example, you might have noticed you ran docker save, while Alice ran docker import. Why does Docker have two seemingly similar but incompatible ways of doing things? Read on to find out!

Saving and loading images

save and load work with Docker images. A Docker image is a kind of template, built from a Dockerfile, that specifies the layers required to build and run an app.

This simple Dockerfile has two instructions corresponding to two layers. The first creates a layer from the busybox image (pulled from Docker Hub(opens in a new tab)), which is an embedded Linux distro. The second is the command you want to run within that environment:

FROM busyboxCMD echo $((40 + 2))Saving

To share or back up the Docker image, use the docker save command. The documentation(opens in a new tab) describes save as follows:

docker save— Save one or more images to a tar archive (streamed to STDOUT by default)

Save your image and inspect its contents (you could instead use docker inspect here, but it can be useful to know that the image just boils down to a list of files):

$ docker save calc > calc.tar$ mkdir calc && tar -xf calc.tar -C calc$ tree calccalc├── 41bfa732a8db4acc9d0ac180f869e1e253176b84748ba5a64732bd5b2ce8 # <- busybox layer│ ├── VERSION│ ├── json│ └── layer.tar├── 889226dbb27fd9ef2765ed48724bf22eb86b48bb984c2edbdb6f3e021e70.json # <- cmd layer├── manifest.json└── repositories

1 directory, 6 filesThe image has two layers, as expected. The BusyBox layer is more complicated, and as such, contains various files and folders, but the CMD layer is just a single JSON configuration file. This file has a Cmd entry, which is the same CMD specified in the Dockerfile — it’s just prefixed by Docker so that it runs correctly in the environment:

{ ... "config": { ... "Cmd": ["/bin/sh", "-c", "echo $((40 + 2))"], ... }, ...}Now that you understand what images are, have inspected their internals, and know how to save them, it’s time move on to cover loading images into Docker.

Loading

To load an existing image, use the load command. The documentation(opens in a new tab) describes load as follows:

docker load— Load an image from a tar archive or STDIN

To test the saved image, first remove the original calc image from your local Docker registry:

$ docker image lsREPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZEcalc latest c93044af5b09 7 minutes ago 1.22MBbusybox latest 19485c79a9bb 4 weeks ago 1.22MB$ docker image rm c93044af5b09 19485c79a9bb...Then, load the calc image from the saved TAR file:

$ docker load < calc.tar0d315111b484: Loading layer ================================>] 1.441MB/1.441MBLoaded image: calc:latestChecking the local images, you’ll see that calc is present. Note that the busybox image isn’t there, as it’s now contained within calc:

$ docker image lsREPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZEcalc latest 889226dbb27f 2 months ago 1.22MBRunning the imported calc image, you can see it works. Finally, a portable calculator in only a couple hundred lines of Docker configuration:

$ docker run calc42Exporting containers

export works with Docker containers. If Docker image is the template describing your app, containers are the resulting environment created from the template, or the place where your app actually runs. Containers run inside the Docker Engine (or another runtime), which abstracts away the host OS/infrastructure, allowing your apps to “run anywhere.”

Docker automatically creates a container when you run an image. If you check your list of containers, you’ll see calc already listed there. As your app just starts, prints, and then exits, you need to pass the -all flag to also list stopped containers:

$ docker container ls --allCONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATEDa8b14091b4e7 calc '/bin/sh -c echo $(…' 2 minutes agoExporting

To export a container, use the docker export command. The documentation(opens in a new tab) describes export as follows:

docker export— Export a container’s filesystem as a tar archive

Export your container and inspect its contents:

$ docker export a8b14091b4e7 > calc-container.tar$ mkdir calc-container && tar -xf calc-container.tar -C calc-container$ tree -L 1 calc-containercalc-container├── bin├── dev├── etc├── home├── proc├── root├── sys├── tmp├── usr└── var

10 directories, 0 filesAs you can see, this is just a regular old Linux file system — the BusyBox file system created when running your image, to be precise.

Why is this useful? Imagine your app is more complicated and takes a long time to build, or it generates a bunch of compute-intensive build artifacts. If you want to clone or move it, you could rebuild it from scratch from the original image, but it would be much faster to export a current snapshot of it, similar to how you might use a prebuilt binary as opposed to compiling one yourself.

Importing images

While save and load are easy to understand, both accepting and resulting in an image, the relationship between import and export is a little harder to grok.

There’s no way to “import a container” (which wouldn’t make sense, as it’s a running environment). As you saw above, export gives you a file system. import takes this file system and imports it as an image, which can run as-is or serve as a layer for other images. Thus, docker export is similar to an operating system snapshot, and the docker import action resembles restoring from backup.

To import an exported container as an image, use the docker import command. The documentation(opens in a new tab) describes import as follows:

docker import— Import the contents from a tarball to create a filesystem image.

Import your container’s file system image and see what it can do:

$ docker import calc-container.tar calcfs:latest$ docker image lsREPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZEcalcfs latest 27ebbdf82bf8 About a minute ago 1.22MBcalc latest 889226dbb27f 2 months ago 1.22MB$ docker run -t -i calcfs /bin/sh/ # lsbin dev etc home proc root sys tmp usr var/ # echo "we have a shell!"we have a shell!/ #As you can see, Docker happily runs your exported file system, which you can then attach to and explore.

Conclusion

To summarize what you’ve learned:

docker saveworks with Docker images. It saves everything needed to build a container from scratch. Use this command if you want to share an image with others.docker loadworks with Docker images. Use this command if you want to run an image exported withsave. Unlikepull, which requires connecting to a Docker registry,loadcan import from anywhere (e.g. a file system, URLs).docker exportworks with Docker containers, and it exports a snapshot of the container’s file system. Use this command if you want to share or back up the result of building an image.docker importworks with the file system of an exported container, and it imports it as a Docker image. Use this command if you have an exported file system you want to explore or use as a layer for a new image.

When I was new to Docker, this caused me some confusion. Had I RTFM’d a little more, digging into the subcommands, I might have noticed that export only applies to containers, while import, load, and save apply to images:

$ docker container --help | grep -E "(export|import|load|save)" export Export a container\'s filesystem as a tar archive

$ docker image --help | grep -E "(export|import|load|save)" import Import the contents from a tarball to create a filesystem image load Load an image from a tar archive or STDIN save Save one or more images to a tar archive (streamed to STDOUT by default)The result of all this learning is that Nutrient Web SDK is now available on both Docker Hub and npm, meaning first-class PDF support for your web apps is only a docker pull(opens in a new tab) or npm install(opens in a new tab) away.

FAQ

Here are a few frequently asked questions about Docker commands.

What is the difference between Docker import/export and load/save commands?

Docker import/export works with containers, allowing you to import a filesystem image or export a container’s filesystem as a tar archive. Load/save commands work with images, allowing you to load an image from a tar archive or save an image to a tar archive.

When should I use the docker save and load commands?

Use docker save to create a backup or share a Docker image, and docker load to import a saved image into Docker. These commands are useful for distributing images without using a Docker registry.

How do I export a Docker container?

Use the docker export command to export a container’s filesystem as a tar archive. This can be useful for creating a snapshot of a container’s state that can be shared or backed up.

How do I import a Docker image?

Use the docker import command to create an image from a tarball containing a filesystem. This is helpful when you have a filesystem snapshot that you want to use as a base for a new Docker image.

What are some practical use cases for using Docker export/import commands?

Export/import commands are useful for migrating containers between hosts, creating backups of container states, and sharing container environments without relying on a Docker registry.