The Challenges of Changelogs

Table of contents

So, changelogs? You might be thinking: There’s not all that much to say about doing a changelog. After all, it’s just a list of things that changed in a particular release, right? Well, if you want to do it properly, there’s a bit more to it. Here at PSPDFKit, there are quite a few things we had to learn over the years in order to get our changelogs right. We even had to resort to building some custom tools to help us with some of the challenges. In this post, I’m going to tell you all about how we handle changelogs for our products, hopefully saving you a bit of work with having to experiment on your own.

Every Project Needs a Changelog

Keeping a changelog is useful for every software project. Be it libraries, like our main products, or applications(opens in a new tab). According to Wikipedia(opens in a new tab), “A changelog is a log or record of all notable changes made to a project.” While that sounds like what you’d get if you simply copy your Git history or pull request descriptions into a file, it’s more than that. A changelog should be written and curated with the target audience of your product in mind. For a software library, that will be other developers, and for an application, it will be your end users. The changelog should be a concise list that contains just enough details to understandably convey the changes to your audience.

Adding Changelog Entries

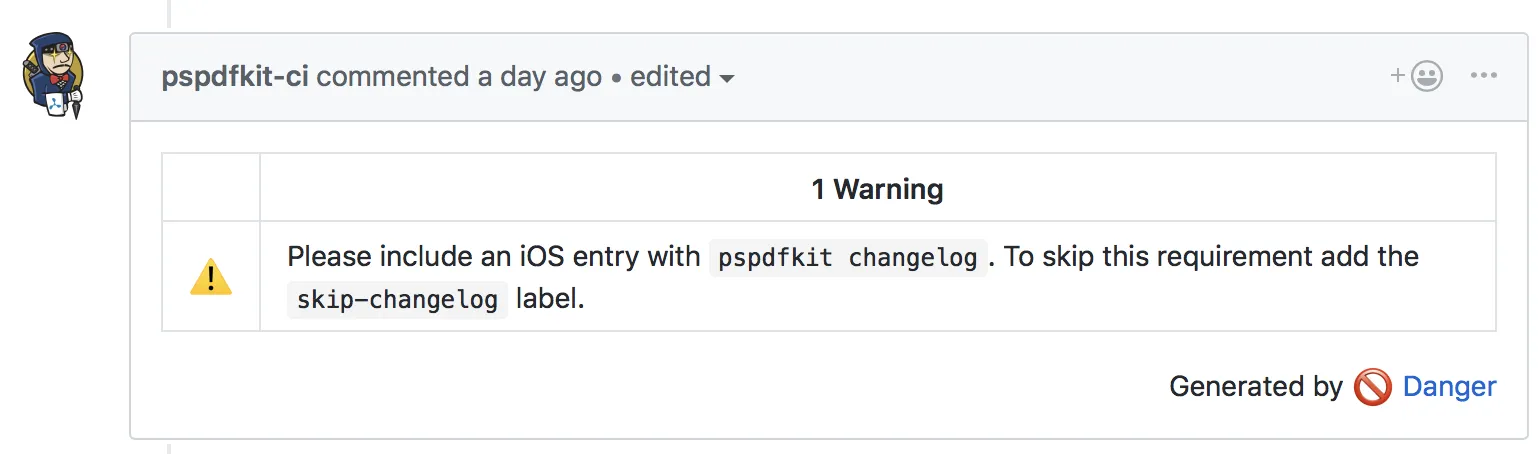

Our teams use GitHub and a pull request-based workflow(opens in a new tab) to develop and review any changes to our products. From the smallest bug fix to the largest new feature, everything gets a new branch and a pull request, where the change is reviewed before it’s merged into our master branch. Part of the review process is also to make sure a changelog entry is both included and appropriate for the change that was made. We set up a Danger(opens in a new tab) script that checks for included changelog entries and warns the author if they’re not included in the pull request.

Some pull requests — like test fixes or additions to unreleased features — don’t require an entry. For those cases, we introduced a skip-changelog pull request label we can apply to silence the Danger checks.

Issues

As our team grew, we quickly realized that putting all changelog entries in one file just didn’t scale well. This is fine for keeping historical records for previous releases, but if many people add new entries in the same places in the changelog, just on different branches, you end up having to resolve many trivial merge conflicts in the changelog. There is a way around this in Git by setting the merge strategy for the changelog to union. However, this is unfortunately not honored by GitHub(opens in a new tab) when merging pull requests.

Another problem we faced was making sure changelogs were correctly backported when doing patch releases. All our development work sooner or later always ends up on our master branch. When we do minor or major releases, we branch off from master and create a stable branch, which is a relatively common approach. If we later need to do a patch release, we cherry-pick relevant changes (merge commits for pull requests we are backporting) from master to our stable branch.

However, in the past, making sure the changelog was correctly backported turned out to be annoying work, always requiring manual labor to ensure the changelog looked good and had no issues, such as duplicate entries. After the release, we would then have to manually remove the entries for the changes we shipped from the master branch changelog. When doing things this way, it was easy to miss a backported entry and just include it as a change in the next release as well.

A Better Way

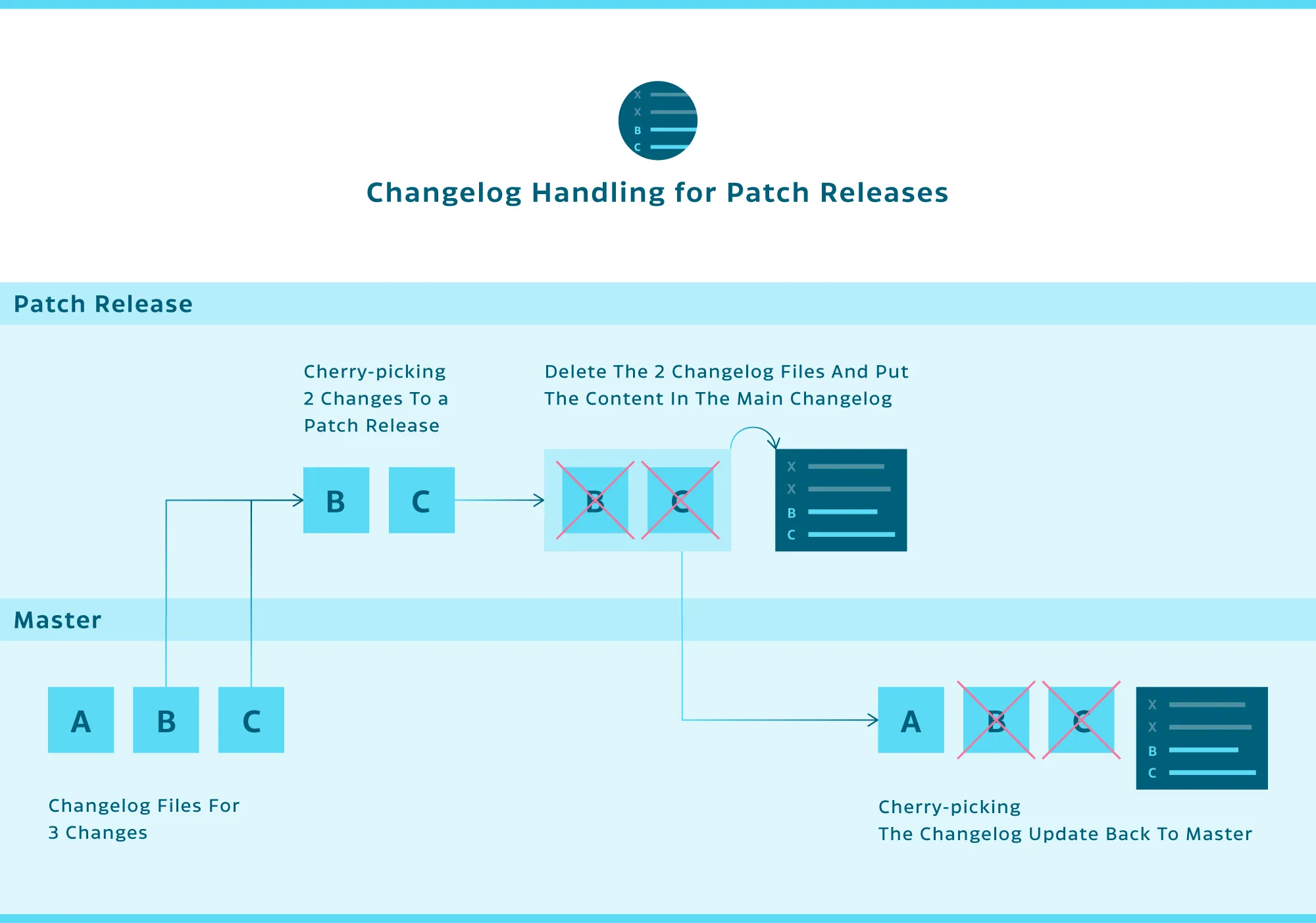

Our solution for the issues outlined above was to split the changelog entries for the current release into multiple files. Every entry would be its own uniquely named file. This process immediately solves the issue with merge conflicts, as Git will automatically union all files in a directory, sidestepping the possibility of any merge conflicts.

To solve the issues with our backporting workflow and to keep our changelog handling infrastructure — which relied on a single changelog file — intact, we added an additional step to our release process. Now when we are ready to release a new version, we take all new changelog files and we merge their contents back into our existing, single, Markdown changelog file. This file contains all the history from previous releases. Then we delete the merged individual changelog files and commit the change into our repository.

The above process works well with our backporting strategy for patch releases. Backported branches will have their changelog files included when the merge commits are cherry-picked into the release branch. There, the files are deleted and their contents are added to the main changelog file. After releasing the patch release, we cherry-pick the changelog update commit back into master, which causes the changelog files for all shipped features to be automatically deleted.

Our Tools

The process outlined above works great and has solved all our major pain points with the changelog. However, we really didn’t want to create and manage all the files manually, as it would be too cumbersome. To help with that, we came up with some command-line helpers to make it much more straightforward.

Adding Entries

The changelog add tool creates uniquely named JSON files that, in addition to containing the actual changelog message, also contain the group, the issue number(s), and an optional sorting priority of the entry. Our SDK is available for multiple platforms, and if an entry affects several platforms, we can add changelog entries to several changelogs with one simple command.

Here’s an example:

pspdfkit changelog add -g pspdfkit -i 1234 1235 -p ios android -m "Fixes a bug"This results in two files (one for iOS and one for Android). The iOS one would look like this:

{ "platform": "ios", "group": "pspdfkit", "issues": [ "1234", "1235" ], "message": "Fixes a bug.", "significance": 5}The files would be named: ios-pspdfkit-1234-1235-Fixes_a_bug_.json and android-pspdfkit-1234-1235-Fixes_a_bug_.json, respectively.

The tool is smart enough to automatically infer the platforms based on the current directory, and it can also open your default editor if you omit the message, just like git commit would do. What’s more is the message can be split into multiple lines as an indented list.

Merging Entries

When it’s finally time to consolidate all the JSON entries into the single changelog file, we just run the following:

pspdfkit changelog generate -p ios -aThe optional -a parameter automatically prepends the new text to the changelog. Otherwise, the new text is just displayed for easier viewing.

The above command will create a new section in our changelog and add the date, version number, and formatted changelog text for all groups. It will also delete the source JSON files. The version number is determined from a special VERSON file that we also use in our build process.

Here’s what we would get if we ran the tool with the single entry from the example above:

### 8.0.0-dev - 31 Jul 2018

#### PSPDFKit

* Fixes a bug. (#1234, #1235)The outlined workflow and above tools have been a real timesaver for us. While they are still pretty custom-tailored and integrated into our other helpers, they could still be extracted and generalized enough to be applicable for a broader audience. If something like this would be useful to you, be sure to let me know via Twitter(opens in a new tab)!

Our Changelog Format

All our PSPDFKit SDKs have their own changelogs published on their respective websites. Our iOS framework has a changelog reaching back to 2011. What you see on the website is backed by a single markdown file with more than 6,000 lines of text. While this is admittedly a lot, it’s way less than the millions of lines we’d get if we instead published our commit messages. The CHANGELOG.md file is part of our source code repository and it’s copied to our website whenever we do a release.

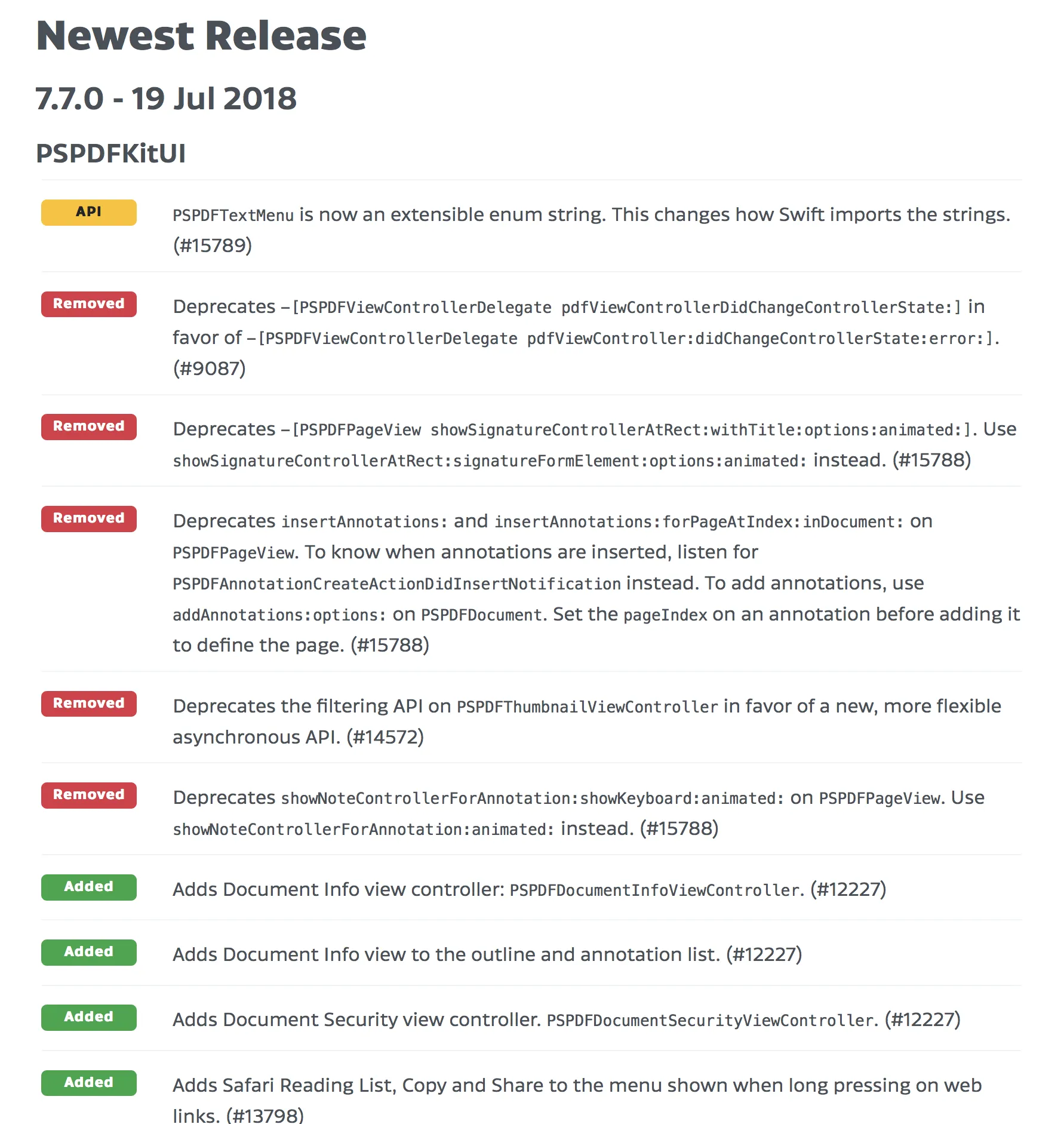

| Website Changelog | Changelog Source |

|---|---|

|  |

Our changelog entries are grouped by releases, and then further down, by sub-frameworks that make up our SDK for a particular problem. However, what should be even more apparent is that they are all written in a particular style and grouped by change type. We also reference our internal issue numbers on every changelog entry. This makes it easier for us both to associate an entry with a particular change in the source code, and to help clients identify if their reported issues were fixed. Again, in this case, it’s a changelog for our framework customers, and it’s written with their needs in mind.

Returning back to the changelog style, we actually formally defined our changelog style, as well as other changelog-specific know-how, in an internal document. Here’s a small extract from the Style section of that guide:

- Use active language and present tense:

Adds feature XYZ.orImproves handling of ABC. - We use tags that are generated by considering the first word of the changelog message. These are also used to order changelog entries in groups during changelog generation. Use the following tag groups to specify what kind of change you are adding:

API:— Highlight breaking API changes, such as those that require people to change their implementations. Describe what API changed and what the new usage is. Point to where to get more information if relevant.Deprecates— API deprecations. You can use text similar to the deprecation warnings.Adds— New features.Improvesand everything else — Improvements and changes.Fixes— Bug fixes.

- A particular GitHub issue can have several entries, e.g. both an

Addsentry and anAPI:note. - Don’t use the word “bug.” Instead, use “issue,” “crash,” or “problem.”

- Add a reference number to the changelog entry. Use

#1234for GitHub issues and PRs on the monorepo. UseZ#5678for Zendesk tickets andV#123for Viewer tickets, if no monorepo issue exists. If multiple issues are referenced, combine them like#1234 Z#5678. If no issue exists (this should not happen often), just use the pull request number.

While some of the above guidelines are specific to our setup, I believe a lot of them can apply to any software product.

Of course, along with this standardized format, we occasionally include freeform introductory text that highlights calls to action or information about the most important changes in a release.

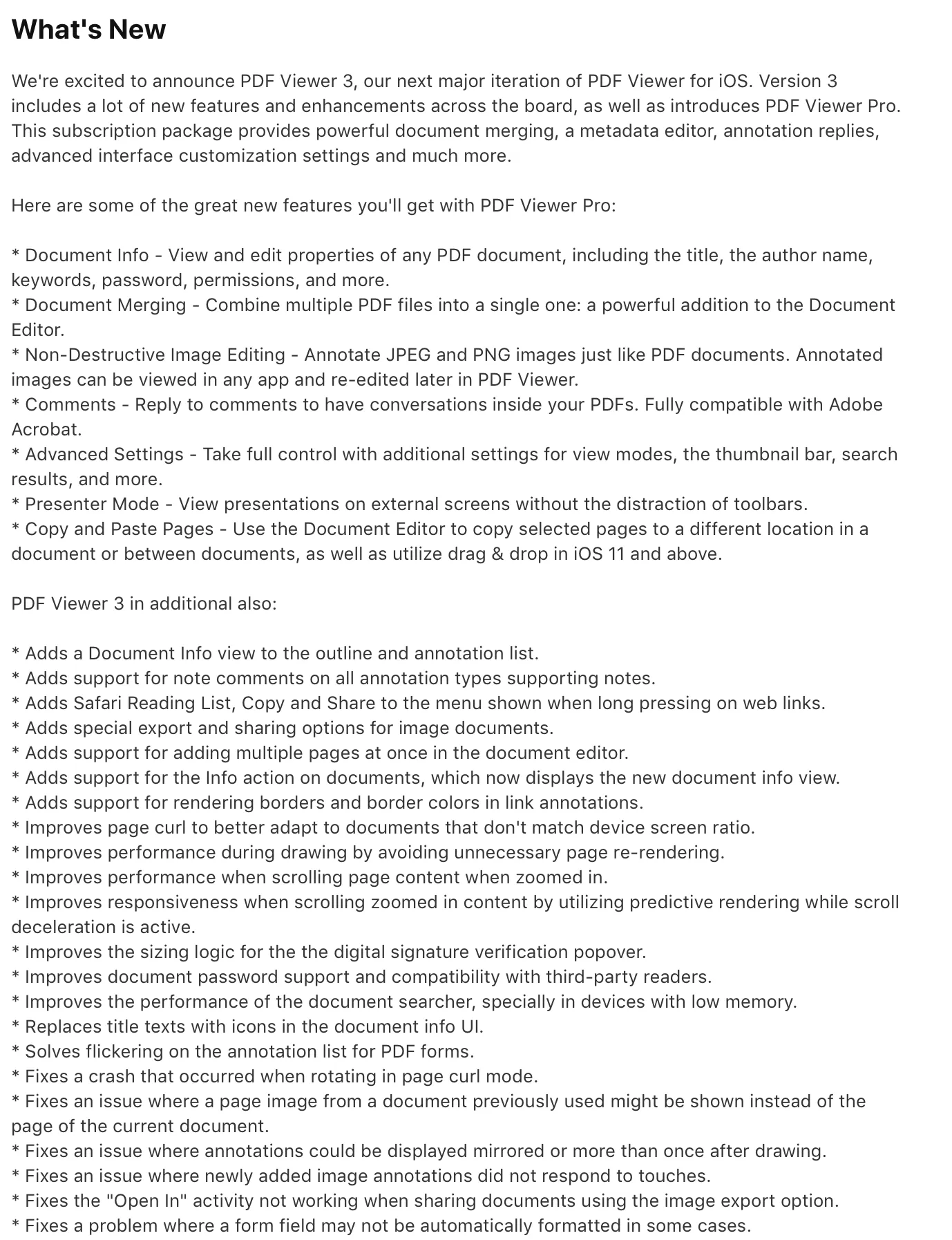

App Changelogs

In addition to our SDK products, we also ship an end user application(opens in a new tab) for iOS and Android. The PDF Viewer has its own changelog for each platform. In there, we note any application-specific changes that are worth mentioning to our users in the What’s New section on the respective app stores. The applications are heavily based on our SDKs, so their release notes are mostly extracted from our SDK changelogs. However, we always make sure to filter, and if needed, reword the content for the different audience we’re targeting. We also always include complementary introduction text.

Many applications like to keep changes under wrap and don’t mention any details in the What’s New sections, or at least keep the content limited to marketing announcements and new features. In part, this is to allow for feature flags and A/B testing. We try to be as open as we can about the changes we’re making, even if that means admitting we had a bug we had to patch. So far, this has worked out well and we’ve only received very positive feedback and praise for the effort we put into this text.

Conclusion

At this point, you should have a fairly good picture of how we handle changelogs at PSPDFKit and why we believe they are important. While they are frequently just a small, often overlooked, and badly maintained part of the software development process, we firmly believe that with the right tools and workflows in place, they can be a great asset, both to your end users and for your team internally.